Gauss’s Law for Magnetic Fields

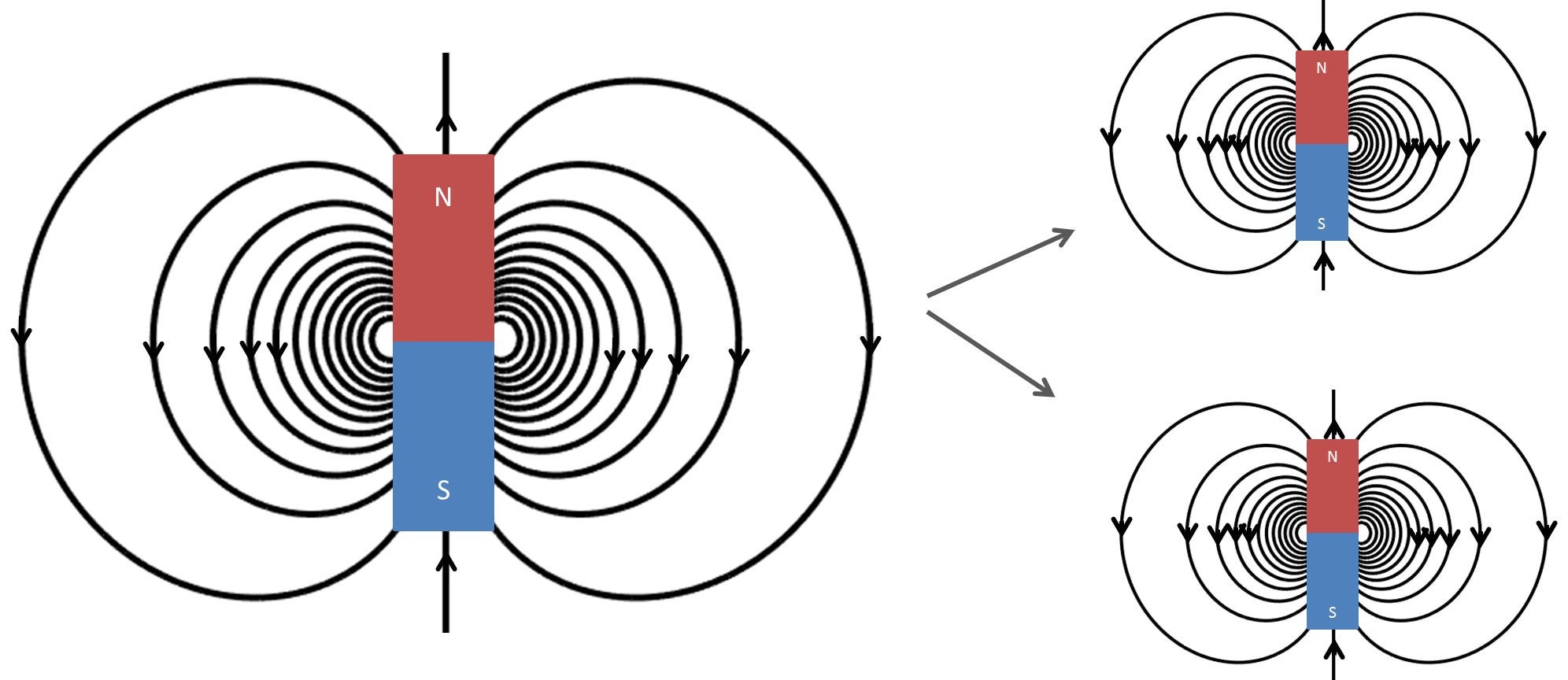

Fig. 34 When a bar magnet is cut in two, you get two bar magnets.

Gauss’s law for magnetism states that no magnetic monopoles exists and that the total flux through a closed surface must be zero. This page describes the time-domain integral and differential forms of Gauss’s law for magnetism and how the law can be derived. The frequency-domain equation is also given. At the end of the page, a brief history of the Gauss’s law for magnetism is provided.

Integral equation

The Gauss’s law for magnetic fields in integral form is given by:

where:

\(\mathbf{b}\) is the magnetic flux

The equation states that there is no net magnetic flux \(\mathbf{b}\) (which can be thought of as the number of magnetic field lines through an area) that passes through an arbitrary closed surface \(S\). This means the number of magnetic field lines that enter and exit through this closed surface \(S\) is the same. This is explained by the concept of a magnet that has a north and a south pole, where the strength of the north pole is equal to the strength of the south pole (Fig. 34). This is equivalent to saying that a magnetic monopole, meaning a solitary north or south pole, does not exist because for every positive magnetic pole, there must be an equal amount of negative magnetic poles.

Differential equation

Gauss’s law for magnetic fields in the differential form can be derived using the divergence theorem. The divergence theorem states:

where \(\mathbf{f}\) is a vector. The right-hand side looks very similar to Equation (48). Using the divergence theorem, Equation (48) is rewritten as follows:

Because the expression is set to zero, the integrand \((\nabla \cdot \mathbf{b})\) must be zero also. Thus the differential form of Gauss’s law becomes:

Derivation using Biot-Savart law

Gauss’s law can be derived using the Biot-Savart law, which is defined as:

where:

\(\mathbf{b}(\mathbf{r})\) is the magnetic flux at the point \(\mathbf{r}\)

\(\mathbf{j}(\mathbf{r'})\) is the current density at the point \(\mathbf{r'}\)

\(\mu_0\) is the magnetic permeability of free space.

Taking the divergence of both sides of Equation (51) yields:

To carry through the divergence of the integrand in Equation (52), the following vector identity is used:

Thus, the integrand becomes:

The first part of Equation (53) is zero as the curl of \(\frac{~\mathbf{\hat{\underline{r}}}}{\lvert \mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r'} \rvert ^2}\) is zero. The second part of Equation (53) becomes zero because \(\mathbf{j}\) depends on \(r'\) and \(\nabla\) depends only on \(r\). Plugging this back into (52), the right-hand side of the expression becomes zero. Thus, we see that:

which is Gauss’s law for magnetism in differential form.

Differential equation in the frequency-domain

The equation can also be written in the frequency-domain as:

Units

Magnetic flux |

\(\mathbf{b}\) |

T |

tesla |

Electric current density |

\(\mathbf{j}\) |

\(\frac{\text{A}}{\text{m}^2}\) |

ampere per square meter |

Constants

Magnetic constant |

\(\mu_0 = 4\pi ×10^{−7} \frac{\text{N}}{\text{A}^2} \approx 1.2566370614...×10^{-6} \frac{\text{T}\cdot \text{m}}{\text{A}}\) |

Discoverers of the law

Gauss’s law for magnetism is a physical application of Gauss’s theorem (also known as the divergence theorem) in calculus, which was independently discovered by Lagrange in 1762, Gauss in 1813, Ostrogradsky in 1826, and Green in 1828. Gauss’s law for magnetism simply describes one physical phenomena that a magnetic monopole does not exist in reality. So this law is also called “absence of free magnetic poles”.

People had long been noticing that when a bar magnet is divided into two pieces, two small magnets are created with their own south and north poles. This can be explained by Ampere’s circuital law: the bar magnet is made of many circular currents rings, each of which is essentially a magnetic dipole; the macroscopic magnetism is from the alignment of the microscopic magnetic dipoles. Because a small current ring always generates an equivalent magnetic dipole, there is no way of generating a free magnetic charge. So far, no magnetic monopole has been found in experiments, despite that many theorists believe a magnetic monopole exists and are still searching for it.

However, as pointed out by Pierre Curie in 1894, magnetic monopoles can exist conceivably. Introducing fictitious magnetic charges to the Maxwell’s equations can give Gauss’s law for magnetism the same appearance as Gauss’s law for electricity, and the mathematics can become symmetric.