Electrical Conductivity

Electrical conductivity is a diagnostic physical property that quantifies how easily electrical charges move through a given material when subjected to an applied electric field. In mathematical development and in references describing rocks or fluids, it is common to use its reciprocal, electrical resistivity. For most of the geophysical surveys described within EM GeoSci, electrical conductivity is the primary diagnostic physical property.

Constitutive Relationship

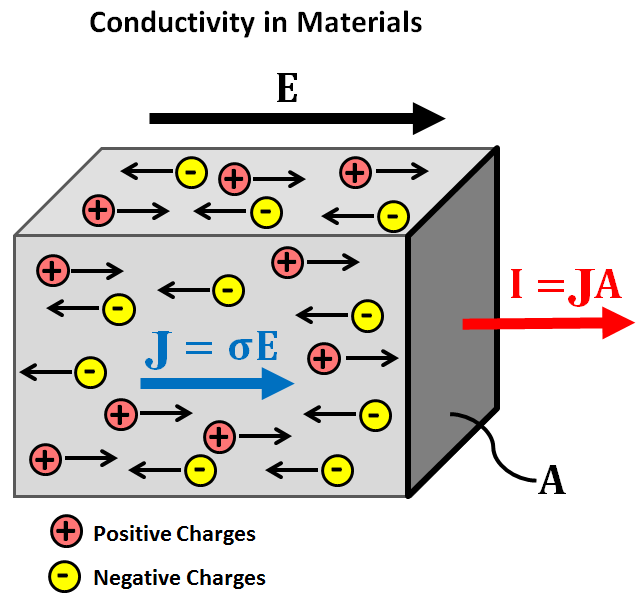

When an electric field is applied to a material, free charges within the material experience an electrical (Coulomb) force. This force causes the free charges to move through the material along the direction of the applied field (i.e. electrical current). The ease at which electrical charges move through a material under the influence of an electric field depends on the material’s electrical conductivity.

Fig. 3 Flow of electrical charges under an applied electric field.

Electrical conductivity \(\sigma\) defines the ratio between the current density \(\mathbf{J}\) within a material and the electric field \(\mathbf{E}\). This relationship is known as Ohm’s law and is given by:

where the current density is defined as the electrical current \(\mathbf{I}\) per unit cross-sectional area \(A\) (Fig. 3):

Electrical Resistivity

In many cases, the electrical properties of a material are characterized using the electrical resistivity \(\rho\). Electrical resistivity is defined as the reciprocal of the electrical conductivity:

Thus the constitutive relationship can be re-expressed as follows:

Chargeability and Frequency-Dependence

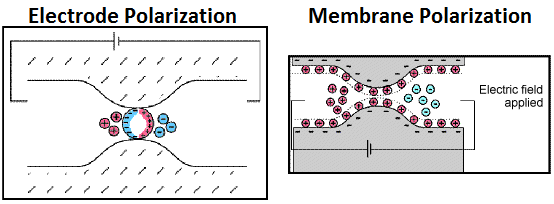

Under the influence of an electric field, free charges (such as ions) flow through materials along the direction of the applied field. For most practical applications, the flow of electrical charges is in phase with the applied electric field. However when ionic charges reach an impermeable barrier, they begin to accumulate. As a result, certain materials can act as capacitors for ionic charges; a phenomenon known as induced polarization. Below are two examples of induced polarization in rocks. On the left, ionic charges accumulate because the pore path is blocked by metallic particles (electrode polarization). On the right, ionic charges accumulate because the pore throat is insufficiently large (membrane polarization).

The degree of charge accumulation (capacitance) under the influence of an external electric field is described as chargeability. Chargeability is frequently considered a separate physical property from conductivity, although the two are related. For chargeable materials, the constitutive relationship (Ohm’s law) becomes frequency-dependent:

A commonly used model for describing frequency-dependent conductivity is the Cole-Cole model:

where \(\sigma_{\infty}\) is the infinite frequency limit, \(0 \leq \eta \leq 1\) is the chargeability, and \(\tau\) and \(0 \leq C \leq 1\) define the rate of charge accumulation. After taking the reciprocal, the electrical resistivity is commonly expressed as:

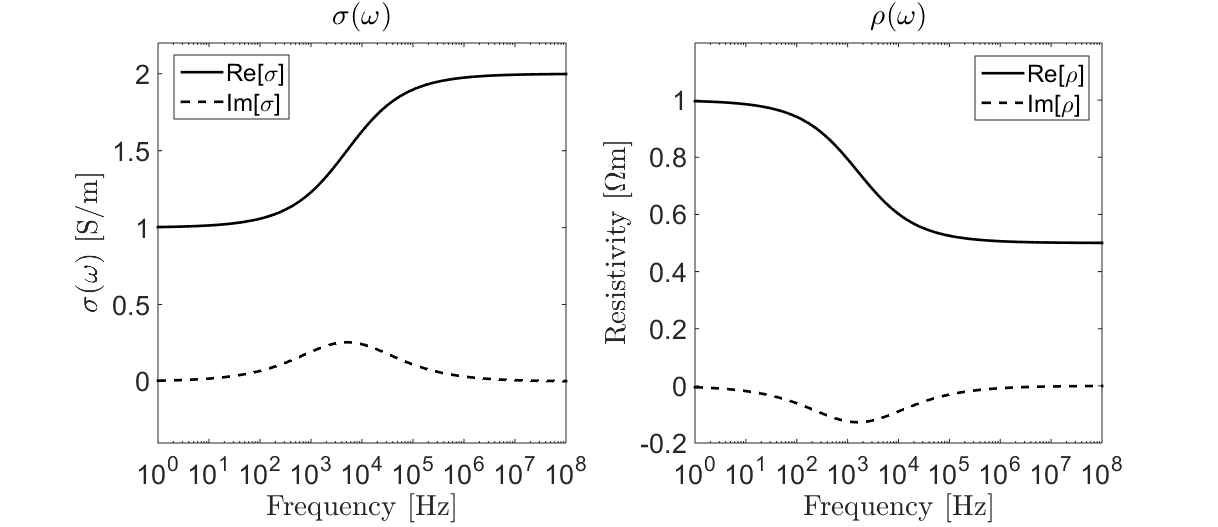

where \(\rho_0\) defines the zero-frequency, or DC, resistivity. Electrical conductivity and resitivity as a function of frequency are illustrated below.

Fig. 4 Cole-Cole conductivity (left) and resistivity (right) for \(\sigma_\infty\) = 2 S/m, \(\rho_0\) = 1 \(\Omega m\), \(\eta\) = 0.5, \(\tau\) = \(10^{-4}\) s and \(C\) = 0.5.

Importance to Geophysics

Electrical Conductivity

The majority of EM surveys exploit contrasts in electrical conductivity to image the subsurface. During direct current resistivity (DCR) surveys for example, electrical current is forced through the Earth. The path taken by the current, as well as the measured data, depend on the subsurface conductivity distribution.

Many EM systems operate on the principles of EM induction. These include: frequency-domain EM (FDEM), time-domain EM (TDEM), marine controlled source EM (CSEM) and unexploded ordnance (UXO) surveys. During these surveys, a transmitter sends time-varying EM signals into the ground which subsequently induce electric currents. The strength of the induced currents and the secondary fields they produce are dependent on the distribution of subsurface conductivities.

Data collected during magnetotelluric (MT) and Z-axis Tipper EM (ZTEM) surveys also depend on the conductivity of the Earth. These methods rely on natural sources to generate EM responses. For MT, the relationships between measured components of the electric and magnetic fields provide insight regarding the Earth’s electromagnetic impedance, and indirectly its electrical conductivity.

Chargeability

In comparison to most other rock types, sulphide-bearing rocks are highly chargeable; one exception being rocks with a high clay content. In sufficient abundances, sulphide-bearing rocks can have significant economic value. Unlike DCR surveys, IP surveys can be used to distinguish chargeable and non-chargeable bodies, even if both are similarly conductive. TDEM systems can also be used to recognize the presence of chargeable bodies, as they produce distinct time-domain responses. As a result, chargeability has become a unique diagnostic physical property used to located sulphide-bearing ore deposits.