Setup

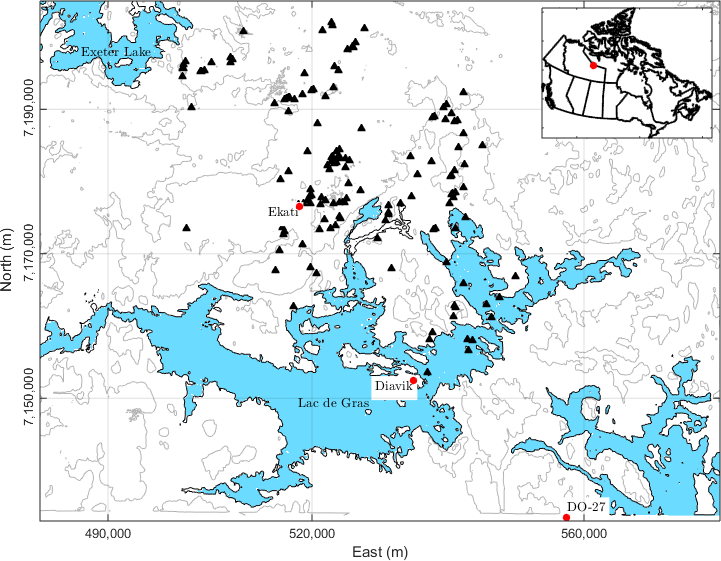

The Northwest Territories in Canada has been surveyed extensively for diamondiferous kimberlites since the early 1980s. The Lac de Gras region has been particularly productive, and hosts two of the largest Canadian deposits: the Ekati and Diavik Diamond Mines. More than 150 kimberlite pipes have been discovered in this region [Pel97] [MWK+02]. Despite this impressive number, it is estimated that less than 10% of those kimberlites are of economic interest. Understanding new deposits early in the exploration program remains an important problem in diamond exploration, as exemplified by the history of the TKC deposit.

Historical background

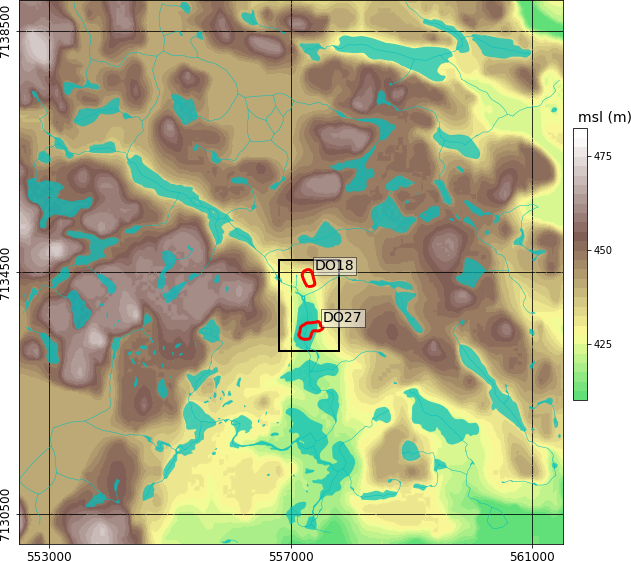

Fig. 359 Topography and hydrology near the DO-27/DO-18 kimberlites. The region of interest (black) and near surface outlines (red) of DO-27 and DO-18 based on drilling are shown for reference.

The early 1990s saw a rush to open Canada’s first diamond mine, and in late 1992, a geophysical airborne survey discovered two kimberlites, called DO-18 and DO-27. At the time of discovery, the area was referred to as the Tli Kwi Cho (TKC) kimberlite complex. Fig. 359 shows the locations of the kimberlites and indicates the extent of DO-27 and DO-18 at the surface based on drilling.

Following the discovery, the interpretation of the two kimberlites evolved over five geologic models, indicative of the uncommon geometry of the deposit [HScottSmithHP09]. What was initial thought to be a large complex was later understood to be disconnected bodies created in multiple volcanic phases. The resource estimate was also revised down over the years as presented in the table below, partially contributing to the Canadian junior stock market crash of 1994 [CPScottSmith06]. At the time of writing, the deposit is owned by Peregrine Diamonds Ltd.

Year |

Resource Estimate (Mt) |

1994 |

50 |

1995 |

25 |

2005-2008 |

30 |

TKC resource estimate over the years. (adapted from [HHSP08]) |

|

The goal of our work is to determine how well our modern-day inversions of geophysical data could have helped the exploration program at the time of discovery. We will attempt to answer the following questions:

How much information could have been extracted form the airborne geophysical data?

Can we differentiate between kimberlite units based on multiple physical properties?

Geological Background

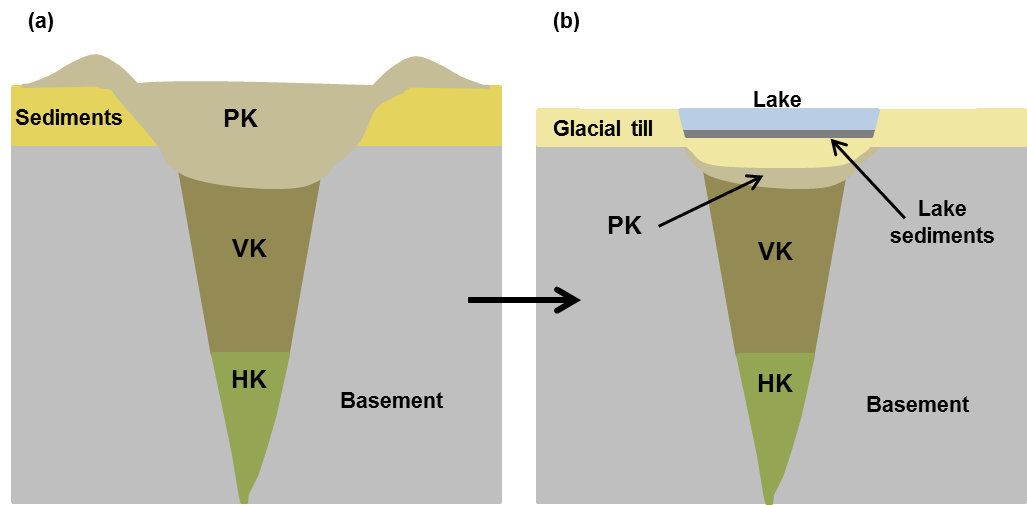

The surrounding lithology at TKC consists of post-Yellowknife Supergroup granite. A thin layer of mudstone covers the granites a the surface [HHBP08]. The Wisconsinan glaciation (Dyke and Prest, 1987) covered the Lac de Gras region with glacial till and ultimately removed the mudstone and part of the PK unit. The erosion that followed the glaciation left approximately 10%-20% of the TKC kimberlite complex exposed at the surface [DKS99], with the rest below a layer of till 5-50 m thick. Fig. 360 shows a conceptual model for a kimberlite pipe in the Lac de Gras region before and after glaciation. A lake was present above DO-27 during the acquisition of the geophysical data.

Fig. 360 Schematic of a typical Lac de Gras kimberlite at (a) emplacement time and (b) after glaciation removed the top layers. A lake may be present after glaciation.

Many different types of kimberlite can exist within a pipe, and unfortunately, there are several classifications and naming conventions [Pel97] [Kja07]. Here, we divide kimberlitic rocks into three types based on their depositional environment:

Hypabyssal (HK): intrusive, igneous, nonfragmented rock, root of the volcanic pipe.

Volcaniclastic (VK): extrusive, fragmental, main volcanic body.

Pyroclastic (PK): a subclass of VK, extrusive, violent, deposited after an explosive event.